During my training in psychology, psychotherapy, and education, I was told not to ask the Why question. I still don’t understand why not. Trying to understand another person’s purpose, values, or thoughts is an extremely valuable quest. I assume we were told not to ask that question because it’s just plain hard to answer. There are other ways to get at purpose, values, and thoughts.

I use the why question now and again. But I rather recently discovered the power of How. It was a true Eureka moment for me when I participated in a five-hour “event” with one of the world’s most renowned personal growth coaches. He would lecture and then, once in a while, go out in the crowd (and it indeed was a crowd!) and talk to individual participants and conduct a mini-coaching session.

All of a sudden, the light goes on in my head. He is asking How instead of What or Why questions. I nearly jumped out of my chair and screamed. Finally, after thirty years of searching, I had discovered a shortcut to successful brief-time coaching. It made so much sense, and I immediately became aware of how I could make my conversations and coaching much clearer, to the point, specific and valuable.

One would think that it’s just fine to ask What questions, and usually, it is enough to have a good conversation.

– What do you enjoy doing?

– What are you good at?

– What would you like to do now?

– What would you like to do more often?

– What’s happening in your life?

– What’s your next step?

– What do you need to do?

– What’s your top priority right now?

– What are you thinking? How are you feeling?

– What choices do you have?

It’s OK to ask these questions. The problem is that the What question most often leads to generalities, not specifics. Connecting values to specifics is the driving force of personal growth and organizational development.

What would you like to do? What do you enjoy doing? Maybe the reply is that I really like listening to music, watching funny videos, playing computer games, training soccer techniques, being with friends, etc. Fine. You can have a brief and rewarding short conversation about what they enjoy doing and ask a few more questions just to understand a bit more about what they get out of it.

“I love that computer game X.” Tell me about how that game is set up. Nothing wrong with that exchange. If, however, you were to ask them how they figured out to get to the next level in the game, they would have to examine their strategies and decision-making. It leads to another level of self-awareness and self-analysis that can be very valuable to enhance in the long term.

“How was the game?” “We won. I had an assist.” “Great! Did you have fun?” “Yeah, feels good to win, right?” All is fine and well. I am just saying that asking about How they made that assist, How they “saw” that opening, and How they made the decision to pass the ball leads to a whole different set of self-reflection. And if they can’t immediately answer, that’s OK to. You are setting the table for later How conversation.

“Thanks for being so nice to Aunt Liza today. I saw you made her smile. How did you do that?”

“You say you finally figured out got your workgroup to finish on time. What was your contribution, and how did you get everyone in the group to finish their part?”

“Thanks for getting your brothers to stop fighting. Tell me how you did that. I’d like to learn!”

“I appreciate the time and effort you put into your learning to play the guitar (violin, game, or whatever). But, how do you get yourself to practice even when you are tired or don’t want to practice?”

Let’s make this visual with the help of what I call a Strength Star.

Here you see a five-pointed start with What on the outside and How on the inside. If you ask your child (friend, colleague, etc.) if you can do a Strength Star with them, ask them the What questions first. “Let’s write up things you enjoy doing or think you are good at doing on the outside of this star.

You hear special energy about one of the points. The example below is with a 12-year-old girl. She likes doing several things, but you sense that “dogs” seems to be a little more special than the other things around the star. So you choose to talk more about her interest in dogs and she tells you that she goes out with the neighbor’s dog, who can be pretty aggressive every once in a while.

You ask the “How” question. So, How do you manage the dog when it gets aggressive? And the girl says, “Well, I need patience, that’s for sure, and I try to talk calmly. But I’m stubborn too, so I can wait until he calms down.”

Dogs – that is one of her interests and activities

How she manages an aggressive dog – is her challenge

The details of How she does the managing – is her strategy

The traits or methods she uses (patience, talking calmly, being stubborn) are her strengths.

These strengths, you can point out, can be used in many other situations. And you may ask about that – or just talk about walking that dog. So you don’t always need to press forward in your conversation.

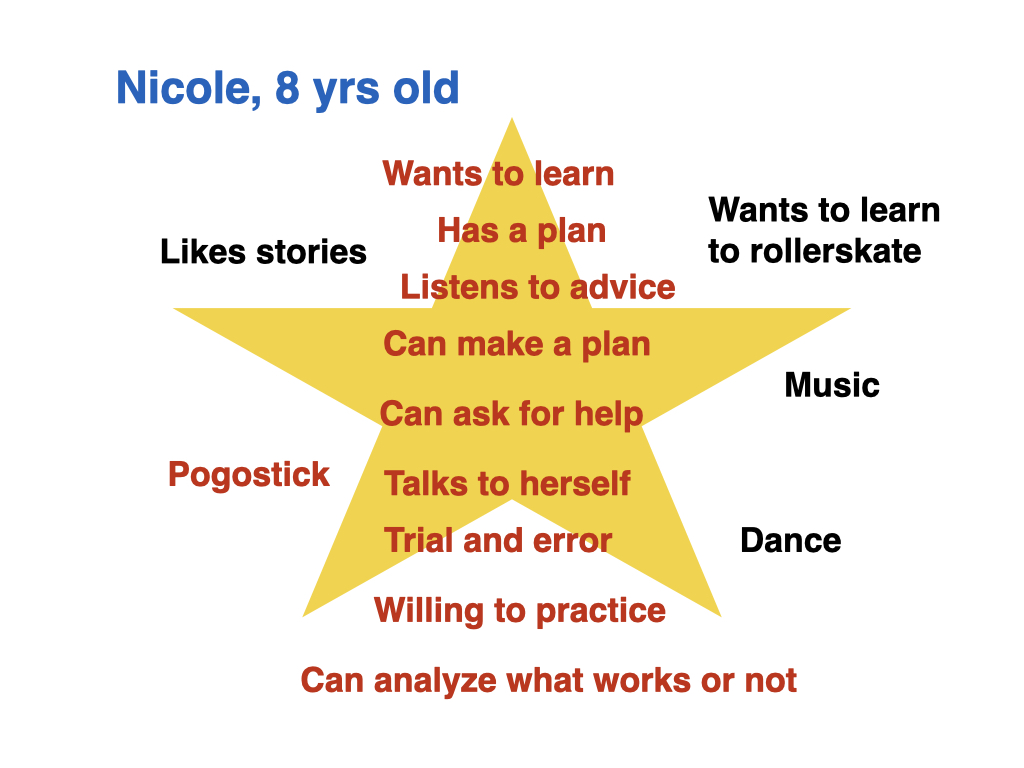

This is what Nicole’s Strength Star looked like (A brief story of Nicole is in the next to last film in the course after the Soccer story). The start describes her learning process, which is quite remarkable for an eight-year-old:

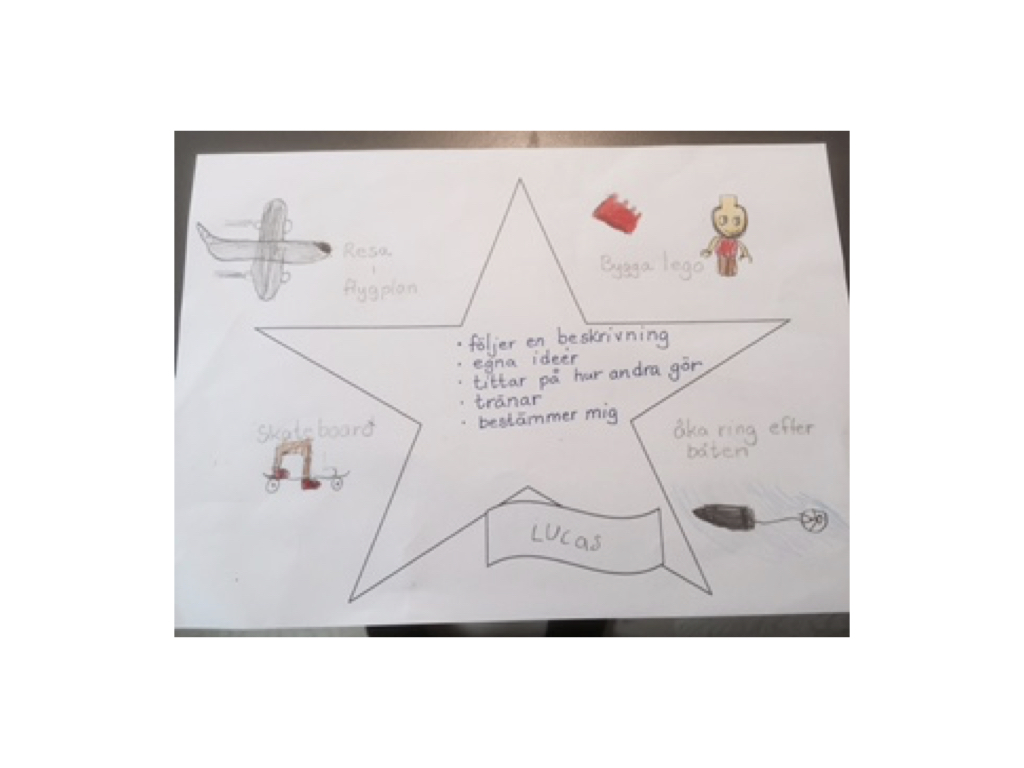

One could also make it with drawings they make or cut-outs from magazines, clipart of photos on the net. Here’s a strength star for a nine-year old:

Obviously, you have to judge the situation at hand and if your talking partner is willing to do a Strength Star. There is nothing wrong with a short conversation about walking the neighbor’s dog. I simply mean that making it visual sends the message about strengths, methods, and personality traits much more clearly and has a greater long-term impact.

“Thanks for telling me how you do X. It was fun to know more about how you go about X. It sure is useful sometimes to be patient and talk calmly (or whatever the keywords are that you hear), and nice to hear you have those skills.”

Discovering How can turn into a very rewarding Eureka Moment. Eureka Moments are the results of your connection, questions, and caring. I remind you not to pressure your son or daughter to answer or dig deeper. Instead, you provide an opportunity to explore their thinking and need to be sensitive to when to leave it be and when to ask a little more.

Homework! Do a Strength Star for yourself about yourself. Then try it out with a good friend. Later, try it with a son or daughter. In another course for teachers, this method will reappear because it can be an extremely valuable tool for teachers in making strengths visible to students and parents.